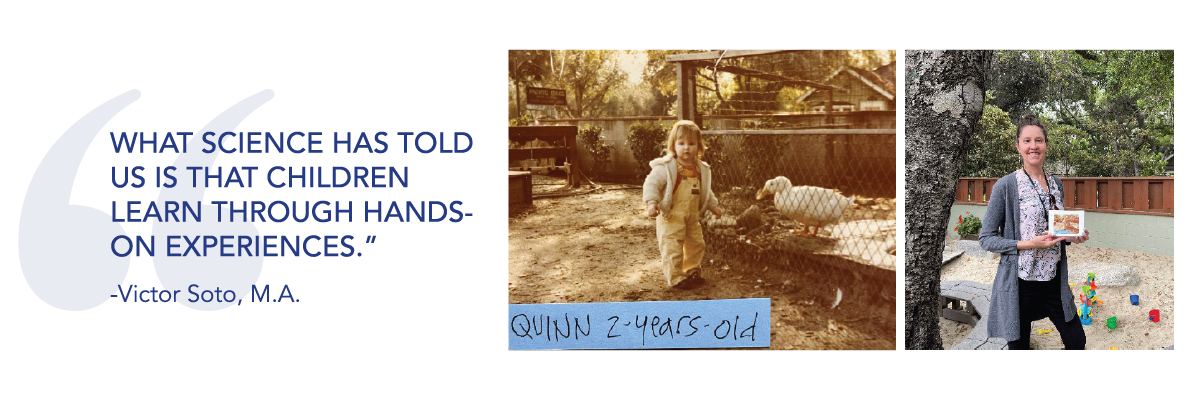

A toddler in yellow overalls, an unzipped spring jacket hanging loose from her shoulders, stands in an open yard next to an enclosure. Beside her, its bill pressed to the wire mesh, is a white duck. The girl is looking toward the camera with mild surprise on her face, as though she has been caught in conversation with her feathered companion. There, outdoors, was a carnival for a child’s senses: the shifting sand and cedar chips under sneakers, the wind rustling through oak tree leaves, sunlight and shadow, and scent of magnolia in the air.

In a second image, the girl, now an adult, stands holding the photograph of her younger self in the same spot where the first picture was taken 40 years earlier. Her name is Quinn Hunter McGonagle, and in the time that passed between the two photographs, she has circled back to Pacific Oaks again and again, from student to artist-in-residence to master teacher to children’s school parent to associate director at Pacific Oaks Children’s School—her present position—and a doctoral candidate at Pacific Oaks College.

In many ways, the circular nature of Hunter McGonagle’s ongoing experiences at Pacific Oaks embodies the inextricable connection between the children’s school and the college. Although Pacific Oaks Children’s School predates the founding of Pacific Oaks College by 13 years, they’re two branches of the same tree, sharing roots anchored in their core values of respect, diversity, social justice, and inclusion. The children’s school and the college developed together and have always worked in concert to build a trusting, loving community that extends far beyond their respective walls. After 80 years of growth, the roots of learning and community at Pacific Oaks are stronger than ever.

Learning Through Play

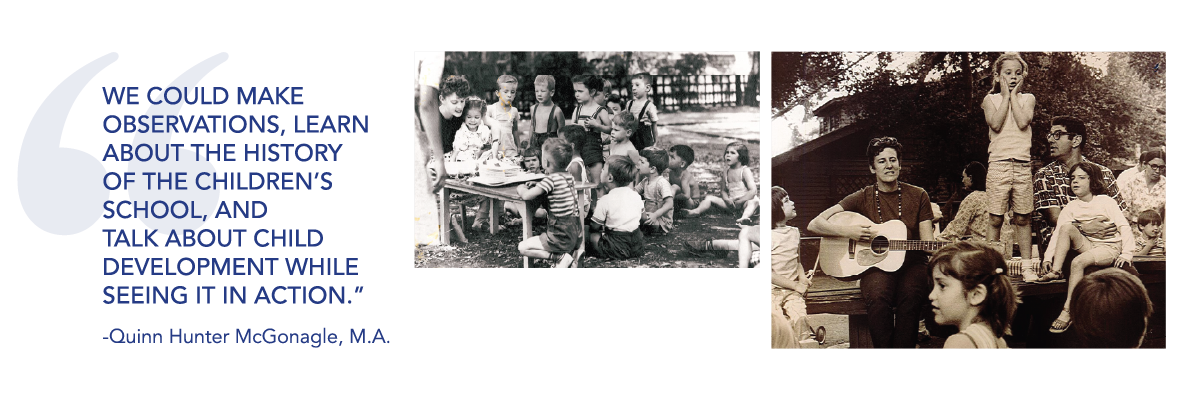

Early black-and-white photographs of Pacific Oaks Children’s School depict young students, dressed in summer clothing, huddled around picnic tables under the Southern California sun and gathered at the feet of a teacher who is singing and playing the guitar. That atmosphere and that style of learning not only endures today but is at the heart of education at both the children’s school and the college.

Elizabeth “Betty” Jones, Ph.D., who began her career as a music teacher at the children’s school and a founding faculty member of the college, pioneered the theory of “emergent curriculum” in 1970, a philosophy of education based on her observations that people, not just children, learn through hands-on experience and self-discovery. In short, it’s based in the idea that children learn through play, so it focuses on flexible educational experiences that engage children with their own interests.

“I always say, ‘Walk around your neighborhood, your school’s neighborhood.’ The children know how to identify the trees that surround our school community,” says Victor Soto, Ed.D., executive director of the Pacific Oaks Children’s School. “They’re acquiring language, and they’re learning about the things they’re exposed to.” While the use of technology, including iPads and computers, is expanding in education, one won’t find any in Pacific Oaks classrooms. “We feel like what science has told us is that children learn through hands-on experiences,” Dr. Soto says.

Pacific Oaks College was founded in 1958 to train teachers in the methods of early childhood education teachers used at the children’s school—Dr. Jones was among the college’s founding faculty members—much of it guided by the students’ questions and interests. The emergence of the college was a natural progression, because the children’s school had been training adults to be teachers since its beginning, even working in partnership with other prestigious institutions such as Cornell University.

The link between the schools’ curricula, then, is baked in. Former children’s school student Hunter McGonagle experienced the cohesion between Pacific Oaks College and the children’s school once she became an educator herself. Having left Pasadena as a young woman to pursue her degree and career in early childhood education elsewhere, Hunter McGonagle eventually returned to Pacific Oaks to become both a teacher in the classroom for 2-year-olds and an adjunct teacher at the college.

“By day, I would be working with the children. Then, in the evenings, I would be teaching the grownups about child development and early child education—about my work with the kids at the children’s school—implementing experiences taken from the daytime job into evening classes with the adult students,” she says.

In seeking permission to meet her college class on the children’s school campus, Hunter McGonagle evoked the practices dating back to earlier times when student teachers from the college trained at the school. (Dr. Jones developed her pedagogy through her observations during such training.) As part of her lesson plan at the college, Hunter McGonagle brought her adult students to the children’s school.

“My class started at 4 p.m., so the students were still able to see some kids playing,” Hunter McGonagle says. “We could make observations, learn about the history of the children’s school, and talk about child development while seeing it in action.”

The Social Justice Component

Pacific Oaks can’t credit its progressive pedagogy alone for the strength of its 80-year-old roots. The institutions also were founded in a firm commitment to building love and trust in the community, a commitment born in part as a direct response to injustices in that community.

During World War II, the Quaker families that had settled in Pasadena, California, in the late 19th century shared their community with a sizable population of Japanese Americans. The pacifist Quakers were appalled to witness the federal government’s actions against their Japanese neighbors, displacing them and interning many throughout the war. Galvanized, a small group of these Quaker families founded what would become the Pacific Oaks Children’s School on the belief that love, tolerance, and peace could be nurtured throughout communities by teaching those values to children from a very young age.

The roots of those values have grounded Pacific Oaks for 80 years. As Judy Krause, Ed.D., associate dean of Human Development and Education, puts it, “There has always been a social justice component at Pacific Oaks.”

Take the groundbreaking work of Louise Derman-Sparks for one example. As late as the 1970s, 80% of grade-school children in the United States, regardless of their family circumstances, learned to read using Dick and Jane readers, books that featured the children of a white, middle-class suburban family. Derman-Sparks, who joined Pacific Oaks’ faculty in 1984, was inspired by her experiences teaching children whose circumstances were very different from Dick’s and Jane’s. She made a case for an “antibias curriculum” that recognizes the harm such education materials can do to children who do not see themselves represented in them. Instead, Derman-Sparks supported the creation of alternative learning materials that reflect our nation’s diversity.

Derman-Sparks’ work continued the spirit of the children’s school founders who confronted discrimination head on, and it served as a beacon to like-minded educators. “After Louise Derman-Sparks’ first book [‘Anti-Bias Curriculum: Tools for Empowering Young Children’] was published, it was like our world exploded,” says Dr. Krause, who had not yet joined Pacific Oaks. “At my school, we were saying, ‘Oh, my God, look at what they’re doing at Pacific Oaks.”

Building on Tradition To Teach the Next Generation

Eighty years after Pacific Oaks’ founding, those in its community have not waned in their commitment to nurturing its roots. Dr. Krause continues to build on its institutional legacy, currently revamping a study Dr. Jones was working on before she died, what Dr. Krause calls the Betty Jones Curriculum Depth Study Group. It involved meeting regularly with a group of educators to discuss their experiences in bringing the emergent curriculum to life in the classroom. “She gave me her permission,” Dr. Krause says. “We’re bringing this work into the 21st century.”

Meanwhile, Pacific Oaks College recently began offering an exciting new degree. After eight decades as a leader in both providing and teaching early childhood education, the college recently launched the Ed.D. in Early Childhood Education program. This program continues and expands on Pacific Oaks’ legacy. And in keeping with the tradition of collaboration between the college and the children’s school, three members of the children’s school staff—Jorge Ramirez, Kiesha Stotko, and, yes, Quinn Hunter McGonagle—are among the first class of students pursuing their Doctor of Education degrees at Pacific Oaks College.

Hunter McGonagle—who was once that little girl in yellow overalls talking with her anatid friend, then was a teacher at the children’s school and the college, and is now a student again in the new Ed.D. program—is well aware of how intertwined with Pacific Oaks her life has been since as long ago as she can recall.

“I have real memories of being here as a kid,” Hunter McGonagle says. “It’s hard to describe in words, but I definitely felt the experience of my childhood education when I was here.” Perhaps that ineffable feeling comes from the trusting, loving Pacific Oaks community, whose roots first took hold 80 years ago and still resonate beneath her feet.